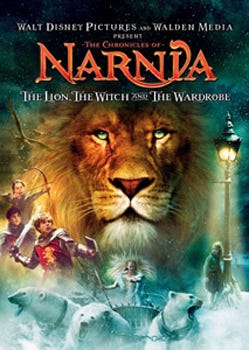

Between his popular books and the 2005 Disney feature, C.S. Lewis is certainly a well-known—and in some circles revered—figure. Atheists and secular humanists were none too happy with the 2005 movie, decrying its public demonstration of religion. By the same token, many conservatives and Christians were defending Lewis’ works to the hilt.

While it would take more than a short essay such as this one to deconstruct the Lewis cult, let this effort serve as some food for thought…

First of all, give Lewis his due. LWW is a pleasant enough story, rich in the mythological tradition so favored by Lewis. But, is it really a Christian allegory? Lewis himself downplayed that aspect of it, and as you shall see, he was right.

Aslan, of course, is the supposed Christ figure, dying to save Edmund, only to come back to life and kill the wicked White Queen. Fair enough, he is raised from the dead by some “deeper magic from before the dawn of time,” and the Queen could represent Satan. The children could even represent the apostles, I guess, but so what?

The idea of Christ as an admired lion and a military leader is diametrically opposed to the notion of the Lamb of God. Indeed, Aslan is far closer to the prevalent Jewish idea of the Messiah than any Christian concept. More than that, besides the Resurrection, Christianity must also provide Salvation. How has anyone been saved? Yes, Aslan breathes on all the frozen victims, representing the Holy Spirit, and brings them back to life, but this is not salvation by any Christian definition.

Worst of all, the children spend some years in Narnia, and are led back to the wardrobe portal by chasing the White Stag. As they return to war-torn England, what has changed? Have they been saved? Have they accepted Aslan/Jesus as their Savior? Who knows? As far as Lewis is concerned, the kids are back from a great adventure; in this case, a Disney adventure—simply another Magic Kingdom.

So, we have an interesting and entertaining fantasy to which “Christian” references can be pasted on after the fact. But, please, how is LWW in any meaningful way Christian? If it is, then a much stronger case can be made for the Matrix films, Melville’s Billy Budd, and even the movie Cool Hand Luke (1967).

LWW is regarded as Christian only because Lewis was already famed as a Christian apologist, which brings us to the next problem.

Many are aware that Lewis was an atheist, who converted in his thirties, largely at the mentoring of his friend J.R.R. Tolkien. And, it was via Lewis’ love of myth that the conversion was to occur. Although he attended the Anglican church, Lewis’ apologetic works only defended a sort of generic Christianity, and were careful to never offend by citing denominational differences. In this, Lewis was a Christian in the model of an English gentleman. As it happened, Lewis preferred the liturgy of the Greek Orthodox church above all others, even though he remained an Anglican.

He would defend Christianity by noting that either Jesus was crazy to say the things he did, or the things he said must be true. And, since he does not sound crazy in the Gospels, then it must be true. This line of reasoning carried over to LWW: Either Lucy is lying about Narnia, or is mad, or she must have seen what she alone at the beginning claimed to see. And, since we know Lucy doesn’t lie, and is not mad, we must believe her.

Frankly, we should expect more from an Oxford don, but this does seem to impress people.

While there is certainly licit Christian theology in Lewis’ apologetic works, he mixes in some real whoppers, none more infamous than his treatment of forgiveness in Mere Christianity. He cites the line from the Lord’s Prayer, “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us,” and concludes, “It is made perfectly clear that if we do not forgive we shall not be forgiven. There are no two ways about it.”

Furthermore, he boldly states that “There is no slightest suggestion that we are offered forgiveness on any other terms.” For such a renowned Christian, this misreading of the Gospel message is no less than stupefying!

Notwithstanding that the Lord’s Prayer petition asks for forgiveness in a spirit of due humility, and is hardly intended as a statement of doctrine, I would assume that Lewis was familiar with the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). The prodigal son returns, repents, and asks his father for acceptance, which I argue is tantamount to asking for forgiveness. He gets it. Is there any other way to explain this parable? Here is the parable according to C.S. Lewis (courtesy of my friend, Catholic apologist Vin Lewis):

Son: “Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you; I no longer deserve to be called your son. Treat me like one of your hired hands.”

Father: “I would like to, son, and I would like to kiss your neck, and give you a ring, but…I am afraid that I cannot! You see, according to C.S. Lewis, a great Christian apologist, I can’t forgive you…unless you forgive others. I represent God in this story.”

Son: “I have to forgive someone?”

Father: “That’s right. Only after you forgive someone can you be forgiven. There are no two ways about it.”

Son: “But no one did anything to me that was wrong. I am the one who is the sinner. I wronged you.”

Father: “I know. Let’s put our Semitic minds together, and maybe we can solve this.”

Want more examples of how C.S. Lewis is wrong about forgiveness?

How about when David confesses that he murdered Uriah, and the prophet Nathan, speaking on God’s behalf tells David that his sins are forgiven. (2 Sam 12:1-13) Whom did David forgive?

Then there’s the part where Jesus, dying on the cross says, “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do.” (Luke 23:34) Whom did the people who put Him to death forgive to achieve such a blessing?

Read the Bible and you will find many more examples that shred Lewis’ position on forgiveness. So, I ask you, was this simply a mistake? But, how could such an eminent scholar make such a “mistake”? Unless, it was not a mistake at all. Worse, and beyond the scope of this article, there are countless examples of bad theology mixed in with the good in his writings.

The only conclusion, using Lewis’ own favorite method of proof, and accepting that he is NOT ignorant of Scripture, is that he is deliberately trying to mislead his readers.

While my findings are not unique, far too many who should know better are still caught up in the C.S. Lewis cult. Perhaps they should just go back to the source material, instead.